Analyzing Performance Data with hpcviewer¶

HPCToolkit provides the hpcviewer (Adhianto, Mellor-Crummey, and Tallent 2010; N. R. Tallent et al. 2011) performance presentation tool for interactive examination of performance databases.

hpcviewer presents a heterogeneous

calling context tree that spans both CPU and GPU contexts, annotated

with measured or derived metrics to help users assess code performance

and identify bottlenecks.

The database generated by hpcprof consists of 4 dimensions: execution context (also called execution profile), time, tree node context, and metric.

We employ the term execution context to include any logical threads (such as OpenMP, pthread and C++ threads), and also MPI processes and GPU streams.

The time dimension represents the timeline of the program’s execution, and tree node context depicts a top-down path in a calling-context tree.

This time dimension is only available if the application is profiled with traces enabled (hpcrun -t option).

Finally, the metric dimension constitutes program measurements performed by hpcrun such as cycles, number of instructions, stall percentages and also some derived metrics such as ratio of idleness.

To simplify performance data visualization, hpcviewer restricts

display two dimensions at a time: the Profile view (Section 10.2) displays

pairs of (tree node context, metric) or (execution context,

metric) dimensions; and the Trace viewer (Section 10.9) visualizes the

behavior of execution contexts over time.

Table below summarizes views supported by hpcviewer.

View |

Dimension |

Note |

|---|---|---|

Profile view - Table |

Tree node context x Metrics |

display the tree and its associated metrics |

Profile view - Thread |

Tree node context x Metrics |

display the tree and its metrics for a set of execution contexts |

Profile view - Graph |

Execution contexts x Metrics |

display a metric of a specific tree node for all execution contexts |

Trace view - Main |

Execution contexts x Time |

display execution context behavior over time |

Trace view - Depth |

Tree node context x Time |

display call stacks over time of an execution context |

Note that in the Profile view, GPU stream execution contexts are not shown in this view; metrics for a GPU operation are associated with the calling context in the thread that initiated the GPU operation (Section 10.6). In the Trace view, GPU streams have their own trace lines independently from their host so that it allows to separate traces between hosts and devices.

Launching¶

Requirements to launch hpcviewer:

On all platforms: Java 11 or newer (up to Java 17).

On Linux: GTK 3.20 or newer.

hpcviewer can either be launched from a command line (Linux platforms) or by clicking the hpcviewer icon (for Windows, Mac OS X and Linux platforms).

The command line syntax is as follows:

hpcviewer [options] [<hpctoolkit-database>]

Here, <hpctoolkit-database> is an optional argument to load a database automatically.

Without this argument, hpcviewer will prompt for the location of a database. Possible options for hpcviewer are shown below:

-h, --helpPrint a help message.

-jh, --java-heapsizeSet the JVM maximum heap size for this execution of

hpcviewer. The value of size must be in megabytes (M) or gigabytes (G). For example, one can specify a size of 3 gigabytes as either 3076M or 3G.-v, --versionPrint the current version

On Linux, when hpcviewer is installed using its install.sh script, which chooses a default maximum size for the Java heap on the current platform. When analyzing measurements for large and complex applications, it may be necessary to use the --java-heap option to specify a larger heap size for hpcviewer to accommodate many metrics for many contexts.

On MacOs and Windows the value of JVM maximum heap size is stored in hpcviewer.ini file, specified with -Xmx option.

On MacOS, this file is located at hpcviewer.app/Contents/Eclipse/hpcviewer.ini.

Profile View¶

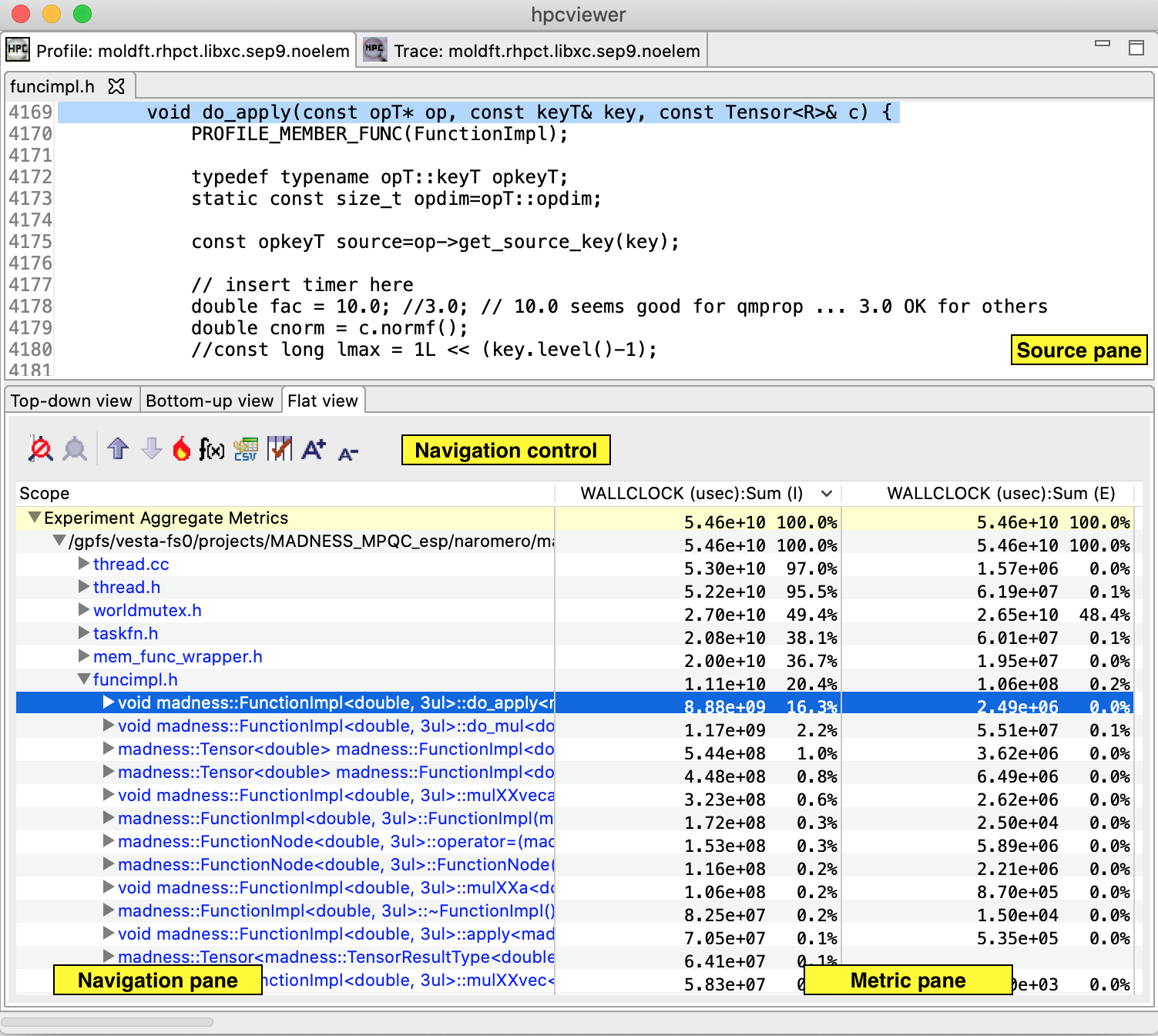

An annotated screenshot of hpcviewer’s interface.¶

This view is the default view and displays pairs of <context, metric> dimensions. It interactively presents context-sensitive performance metrics correlated to program structure and mapped to a program’s source code, if available. It can present an arbitrary collection of performance metrics gathered during one or more runs or compute derived metrics.

Figure 10.1 shows an annotated screenshot of hpcviewer’s user interface presenting a call path profile.

The annotations highlight hpcviewer’s principal window panes and key controls.

The browser window is divided into three panes.

The Source pane (top) displays program source code.

The Navigation and Metric panes (bottom) associate a table of performance metrics with static or dynamic program structure.

These panes are discussed in more detail in Section 10.3.

hpcviewer displays calling-context-sensitive performance data in three different views: a top-down Top-down View, a bottom-up Bottom-up View, and a Flat View.

One selects the desired view by clicking on the corresponding view control tab.

We briefly describe the three views and their corresponding purposes.

Top-down View. This top-down view shows the dynamic calling contexts (call paths) in which costs were incurred. Using this view, one can explore performance measurements of an application in a top-down fashion to understand the costs incurred by calls to a procedure in a particular calling context. We use the term cost rather than simply time since

hpcviewercan present a multiplicity of metrics such as cycles, or cache misses) or derived metrics (e.g. cache miss rates or bandwidth consumed) that that are other indicators of execution cost.A calling context for a procedure

fconsists of the stack of procedure frames active when the call was made tof. Using this view, one can readily see how much of the application’s cost was incurred byfwhen called from a particular calling context. If finer detail is of interest, one can explore how the costs incurred by a call tofin a particular context are divided betweenfitself and the procedures it calls. HPCToolkit’s call path profilerhpcrunand thehpcvieweruser interface distinguish calling context precisely by individual call sites; this means that if a proceduregcontains calls to procedurefin different places, these represent separate calling contexts.Bottom-up View. This bottom-up view enables one to look upward along call paths. The view apportions a procedure’s costs to its callers and, more generally, its calling contexts. This view is particularly useful for understanding the performance of software components or procedures that are used in more than one context. For instance, a message-passing program may call

MPI_Waitin many different calling contexts. The cost of any particular call will depend upon the structure of the parallelization in which the call is made. Serialization or load imbalance may cause long waits in some calling contexts while other parts of the program may have short waits because computation is balanced and communication is overlapped with computation.When several levels of the Bottom-up View are expanded, saying that the Bottom-up View apportions metrics of a callee on behalf of its callers can be confusing. More precisely, the Bottom-up View apportions the metrics of a procedure on behalf of the various calling contexts that reach it.

Flat View. This view organizes performance measurement data according to the static structure of an application. All costs incurred in any calling context by a procedure are aggregated together in the Flat View. This complements the Top-down View, in which the costs incurred by a particular procedure are represented separately for each call to the procedure from a different calling context.

Panes¶

hpcviewer’s browser window is divided into three panes: the Navigation pane, Source pane, and the Metrics pane.

We briefly describe the role of each pane.

Source Pane¶

The source pane displays the source code associated with the current entity selected in the navigation pane.

When a performance database is first opened with hpcviewer, the source pane is initially blank because no entity has been selected in the navigation pane.

Selecting any entity in the navigation pane will cause the source pane to load the corresponding file, scroll to and highlight the line corresponding to the selection.

Switching the source pane to view to a different source file is accomplished by making another selection in the navigation pane.

Metric Pane¶

The metric pane displays one or more performance metrics associated with entities to the left in the navigation pane.

Entities in the tree view of the navigation pane are sorted at each level of the hierarchy by the metric in the selected column.

When hpcviewer is launched, the leftmost metric column is the default selection and the navigation pane is sorted according to the values of that metric in descending order.

One can change the selected metric by clicking on a column header.

Clicking on the header of the selected column toggles the sort order between descending and ascending.

During analysis, one often wants to consider the relationship between two metrics. This is easier when the metrics of interest are in adjacent columns of the metric pane. One can change the order of columns in the metric pane by selecting the column header for a metric and then dragging it left or right to its desired position. The metric pane also includes scroll bars for horizontal scrolling (to reveal other metrics) and vertical scrolling (to reveal other scopes). Vertical scrolling of the metric and navigation panes is synchronized.

Understanding Metrics¶

hpcviewer can present an arbitrary collection of performance metrics gathered during one or more runs, or compute derived metrics expressed as formulae. A derived metric may be specified with a formula that typically uses one or more existing metrics as terms in an expression.

For any given scope in hpcviewer’s three views, hpcviewer computes both inclusive and exclusive metric values.

First, consider the Top-down View.

Inclusive metrics reflect costs for the entire subtree rooted at that scope.

Exclusive metrics are of two flavors, depending on the scope.

For a procedure, exclusive metrics reflect all costs within that procedure but excluding callees.

In other words, for a procedure, costs are exclusive with respect to dynamic call chains.

For all other scopes, exclusive metrics reflect costs for the scope itself; i.e., costs are exclusive with respect to static structure.

The Bottom-up and Flat Views contain inclusive and exclusive metric values that are relative to the Top-down View.

This means, e.g., that inclusive metrics for a particular scope in the Bottom-up or Flat View are with respect to that scope’s subtree in the Top-down View.

How Metrics are Computed¶

Call path profile measurements collected by hpcrun correspond directly to the Top-down View.

hpcviewer derives all other views from exclusive metric costs in the Top-down View.

For the Bottom-up View, hpcviewer collects the cost of all samples in each function and attribute that to a top-level entry in the Bottom-up View.

Under each top-level function, hpcviewer can look up the call chain at all of the context in which the function is called.

For each function, hpcviewer apportions its costs among each of the calling contexts in which they were incurred.

hpcviewer computes the Flat View by traversing the calling context tree and attributing all costs for a scope to the scope within its static source code structure.

The Flat View presents a hierarchy of nested scopes for load modules, files, procedures, loops, inlined code and statements.

Example¶

Note

// file1.c

f () {

g ();

}

// m is the main routine

m () {

f ();

g ();

}

// file2.c

// g can be a recursive function

g () {

if ( . . ) g ();

if ( . . ) h ();

}

h () {

}

A sample program divided into two source files.

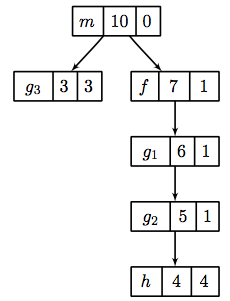

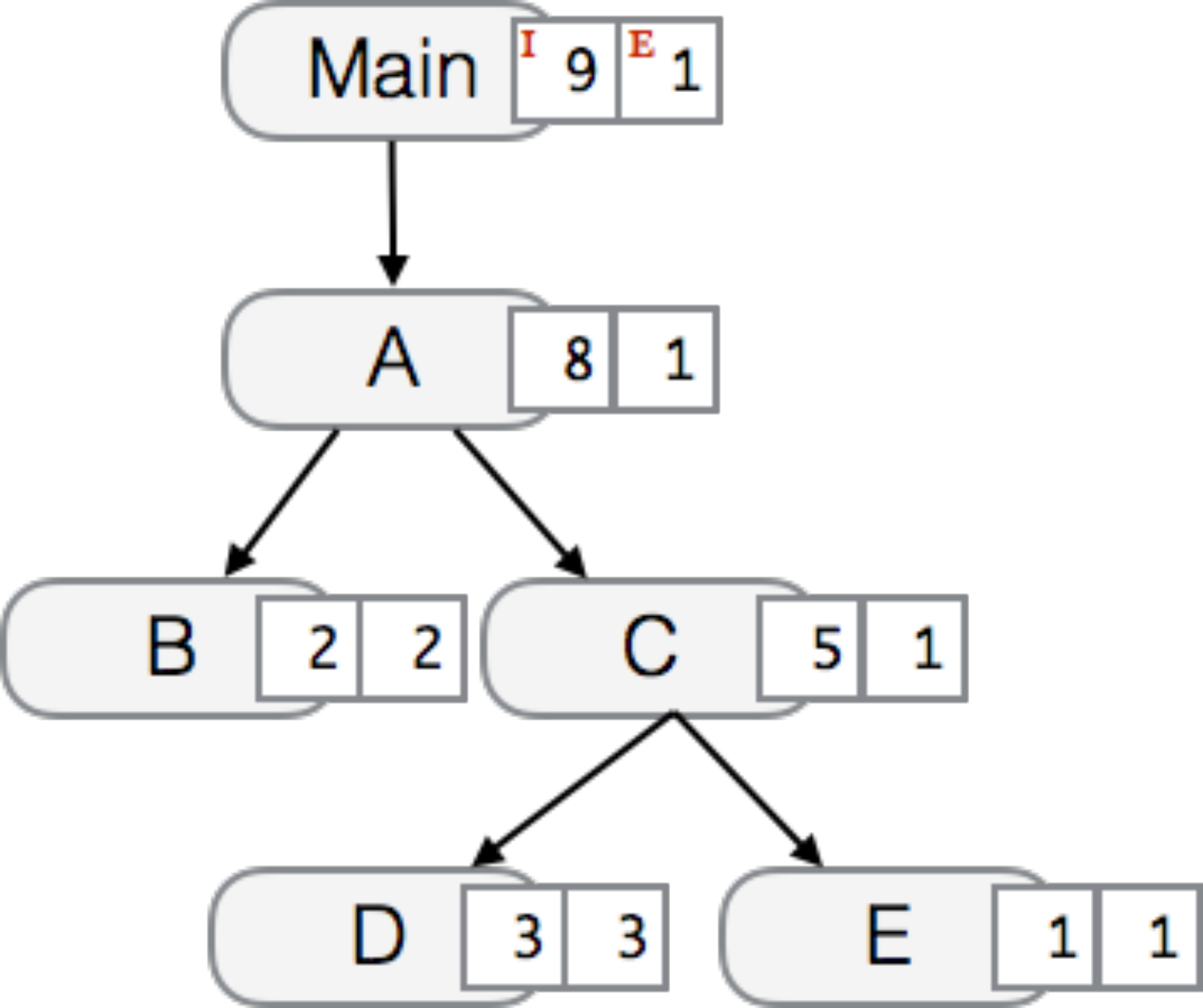

Top-down View. Each node of the tree has three boxes: the left-most is the name of the node (or in this case the name of the routine, the center is the inclusive value, and on the right is the exclusive value.¶

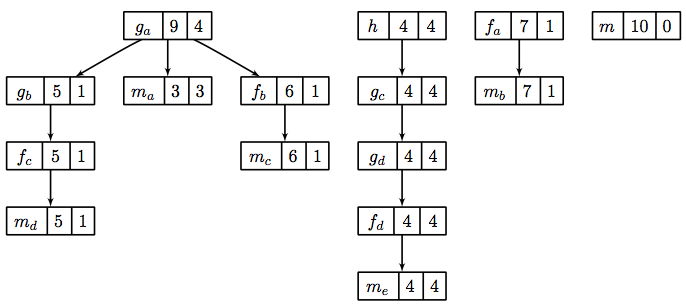

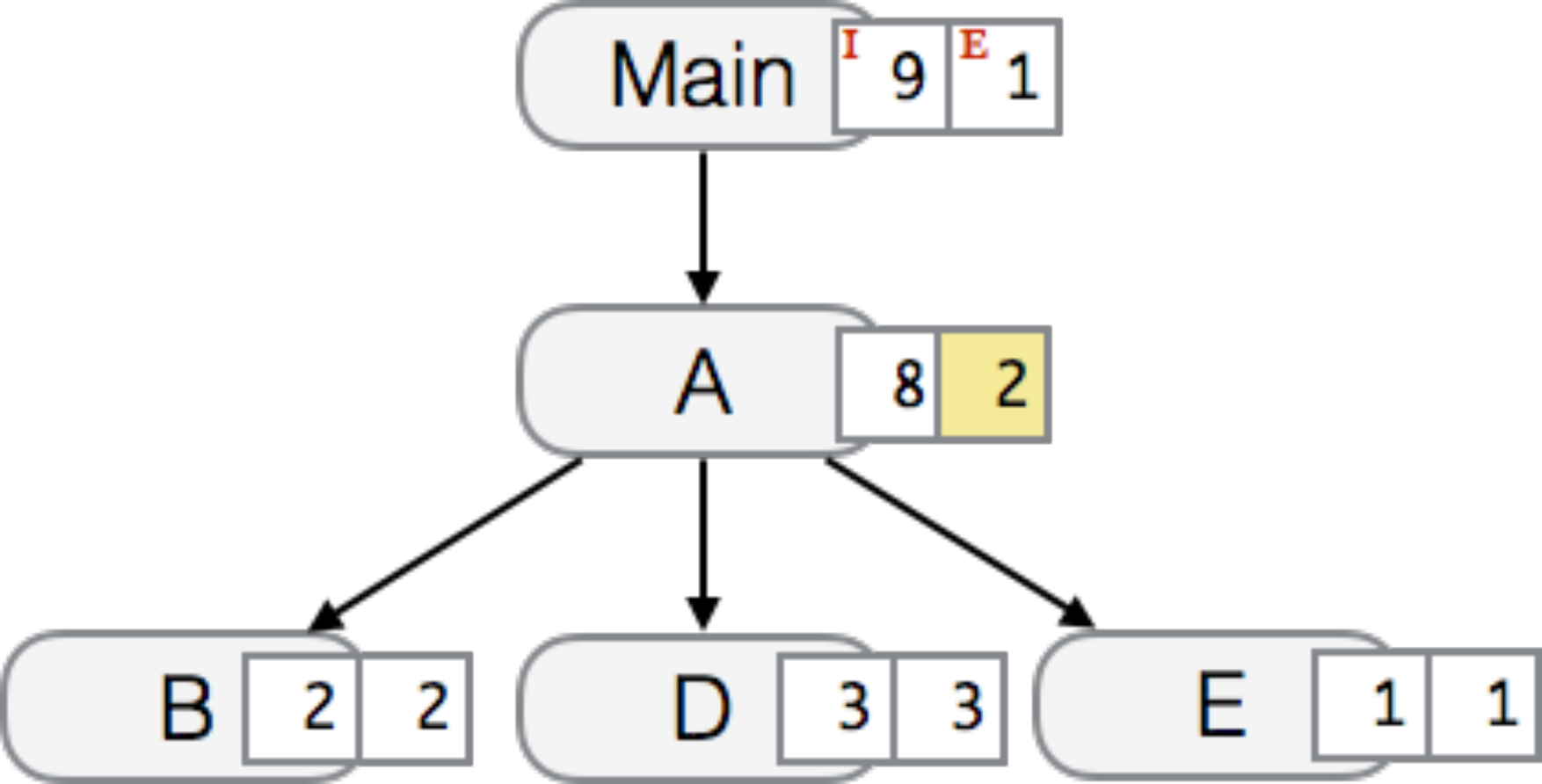

Bottom-up View¶

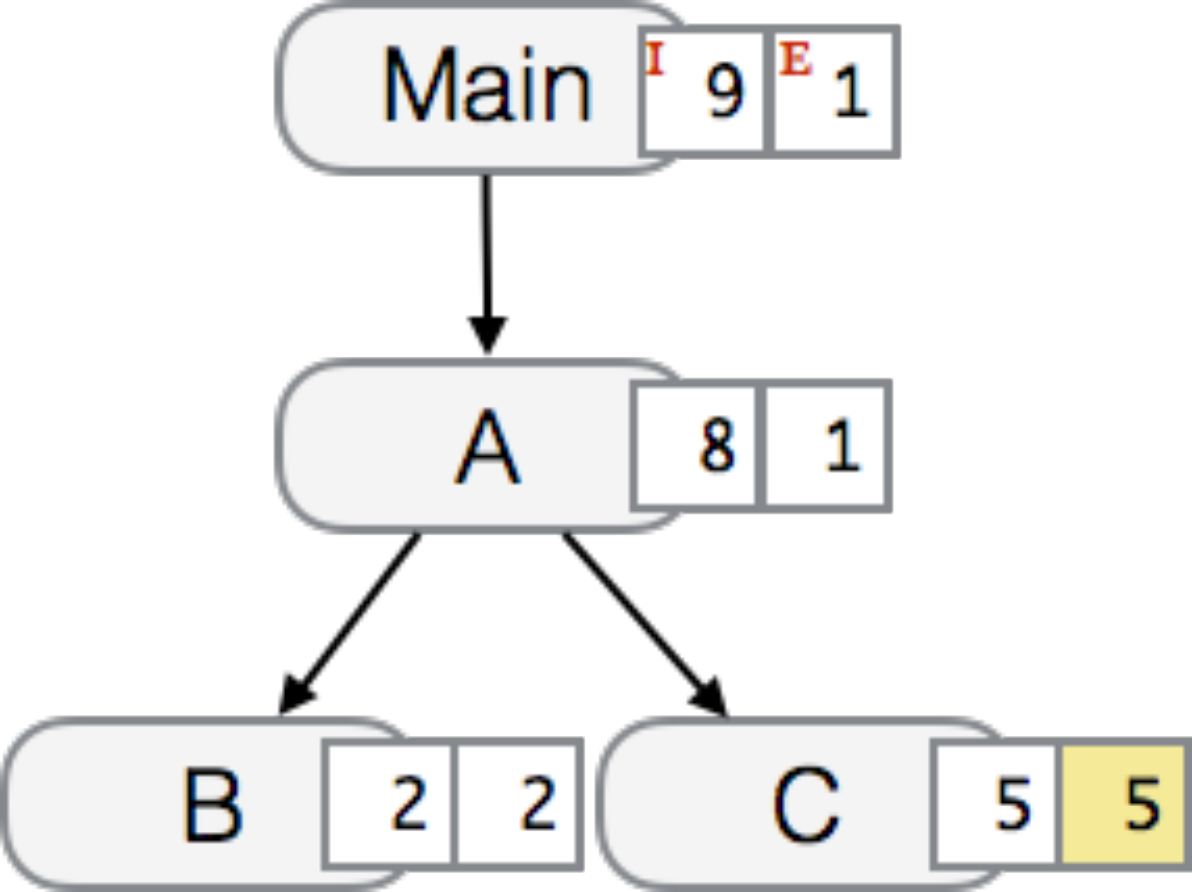

Flat View¶

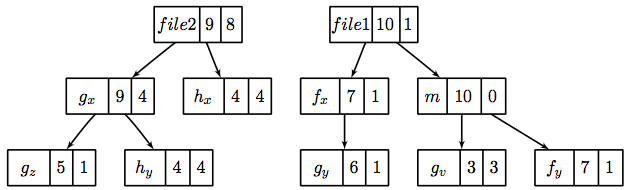

Figure 10.2 shows an example of a recursive program separated into two files, file1.c and file2.c.

In this figure, we use numerical subscripts to distinguish between different instances of the same procedure.

In the other parts of this figure, we use alphabetic subscripts.

We use different labels because there is no natural one-to-one correspondence between the instances in the different views.

Routine g can behave as a recursive function depending on the value of the condition branch (lines 3–4).

Figure 10.3 shows an example of the call chain execution of the program annotated with both inclusive and exclusive costs.

Computation of inclusive costs from exclusive costs in the Top-down View involves simply summing up all of the costs in the subtree below.

In this figure, we can see that on the right path of the routine m, routine g (instantiated in the diagram as g_1) performed a recursive call (g_2) before calling routine h.

Although g_1, g_2 and g_3 are all instances from the same routine (i.e., g), we attribute a different cost for each instance.

This separation of cost can be critical to identify which instance has a performance problem.

Figure 10.4 shows the corresponding scope structure for the Bottom-up View and the costs we compute for this recursive program.

The procedure g noted as g_a (which is a root node in the diagram), has different cost to g as a callsite as noted as g_b, g_c and g_d.

For instance, on the first tree of this figure, the inclusive cost of g_a is 9, which is the sum of the highest cost for each path in the calling context tree shown in Figure 10.3 that includes g: the inclusive cost of g_3 (which is 3) and g_1 (which is 6).

We do not attribute the cost of g_2 here since it is a descendant of g_1 (in other term, the cost of g_2 is included in g_1).

Inclusive costs need to be computed similarly in the Flat View.

The inclusive cost of a recursive routine is the sum of the highest cost for each branch in calling context tree.

For instance, in Figure 10.5, The inclusive cost of g_x, defined as the total cost of all instances of g, is 9, and this is consistently the same as the cost in the bottom-up tree.

The advantage of attributing different costs for each instance of g is that it enables a user to identify which instance of the call to g is responsible for performance losses.

Derived Metrics¶

Frequently, the data become useful only when combined with other information such as the number of instructions executed or the total number of cache accesses.

While users don’t mind a bit of mental arithmetic and frequently compare values in different columns to see how they relate for a scope, doing this for many scopes is exhausting.

To address this problem, hpcviewer provides a mechanism for defining metrics.

A user-defined metric is called a “derived metric.”

A derived metric is defined by specifying a spreadsheet-like mathematical formula that refers to data in other columns in the metric table by using $n to refer to the value in the nth column.

Formulae¶

The formula syntax supported by hpcviewer is inspired by spreadsheet-like in-fix mathematical formulae.

Operators have standard algebraic precedence.

Examples¶

Suppose the database contains information from five executions, where the same two metrics were recorded for each:

Metric 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8: total number of cycles

Metric 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9: total number of floating point operations

To compute the average number of cycles per floating point operation across all of the executions, we can define a formula as follows:

avg($0, $2, $4. $6. $8) / avg($1, $3, $5, $7, $9)

Creating Derived Metrics¶

Derived metric dialog box¶

A derived metric can be created by clicking the Derived metric tool item in the navigation/control pane. A derived metric window will then appear as shown in Figure 10.6.

The window has two main parts:

Derived metric definition, which consists of:

New name for the derived metric. Supply a string that will be used as the column header for the derived metric. If you don’t supply one, the metric will have no name.

Formula definition field. In this field the user can define a formula with spreadsheet-like mathematical formula. This field must be filled. A user can type a formula into this field, or use the buttons in the Assistance pane below below to help insert metric terms or function templates.

Metrics. This is used to find the ID of a metric. For instance, in this snapshot, the metric

WALLCLOCKhas the ID2. By clicking the button Insert metric, the metric ID will be inserted in formula definition field. A metric may refer to the value at an individual node in the calling context tree (point-wise) or the value at the root of the calling context tree (aggregate).Functions. This is to guide the user who wants to insert functions in the formula definition field. Some functions require only one metric as the argument, but some can have two or more arguments. For instance, the function

avg()which computes the average of some metrics, needs at least two arguments.

Advanced options:

Augment metric value display with a percentage relative to column total. When this box is checked, each scope’s derived metric value will be augmented with a percentage value, which for scope s is computed as the 100 * (s’s derived metric value) / (the derived metric value computed by applying the metric formula to the aggregate values of the input metrics for the entire execution). Such a computation can lead to nonsensical results for some derived metric formulae. For instance, if the derived metric is computed as a ratio of two other metrics, the aforementioned computation that compares the scope’s ratio with the ratio for the entire program won’t yield a meaningful result. To avoid a confusing metric display, think before you use this button to annotate a metric with its percent of total.

Default format. This option will display the metric value using scientific notation with three digits of precision, which is the default format.

Display metric value as percent. This option will display the metric value formatted as a percent with two decimal digits. For instance, if the metric has a value 12.3415678, with this option, it will be displayed as 12.34%.

Custom format. This option will present the metric value with your customized format. The format is equivalent to Java’s Formatter class, or similar to C’s printf format. For example, the format “

%6.2f” will display six digit floating-points with two digits to the right of the decimal point.

Note that the entered formula and the metric name will be stored automatically. One can then review again the formula (or metric name) by clicking the small triangle of the combo box.

Metrics in Execution-context level¶

Execution context is an abstract concept of a measurable code execution. For example, in a pure MPI application, an execution context is an MPI rank, while an execution context of an OpenMP application is an OpenMP thread, and an execution context of GPU applications can be a GPU stream. For hybrid MPI+OpenMP applications, its execution context is its MPI rank and its OpenMP master and worker threads.

There are two types of execution context: physical such as NODE and CORE, and logical like RANK, THREAD, GPUCONTEXT and GPUSTREAM. NODE is the id of the compute node, RANK is the rank of the process (like MPI), CORE is the CPU core where the application thread is bound to, THREAD is the application CPU thread (such as OpenMP thread), GPUCONTEXT is a context used to access a GPU (like GPU device), and GPUSTREAM is a stream or queue used to push work to a GPU.

Plot Graphs¶

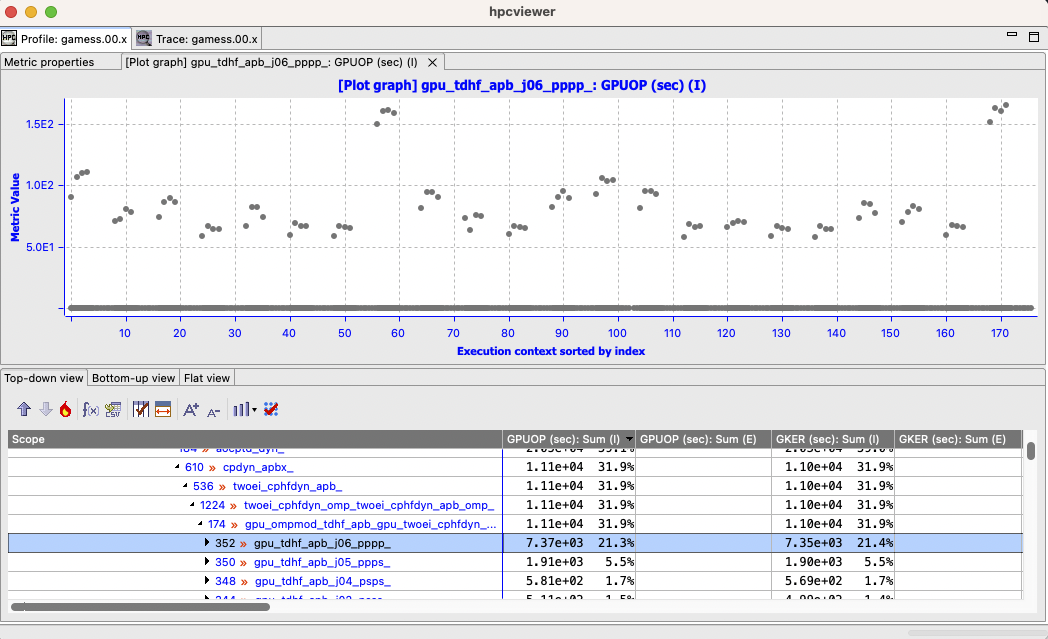

Plot graph view of a procedure in GAMESS MPI+OpenMP application showing a imbalance where a group of execution contexts have much higher GPU operations than others.¶

HPCToolkit Experiment databases that have been generated by hpcprof can be used by hpcviewer to plot graphs of metric values for each execution context.

This is particularly useful for quickly assessing load imbalance in context across the several threads or processes of an execution.

Figure 10.7 shows hpcviewer rendering such a plot.

The horizontal axis shows application execution context sorted by index (in this case it’s MPI rank and OpenMP thread).

The vertical axis shows metric values for each execution context.

Because hpcviewer can generate scatter plots for any node in the Top-down View, these graphs are calling-context sensitive.

To create a graph, first select a scope in the Top-down View; in the Figure 10.7, the procedure gpu_tdhf_apb_j06_pppp_ is selected.

Then, click the graph button  to show the associated sub-menus.

At the bottom of the sub-menu is a list of metrics that

to show the associated sub-menus.

At the bottom of the sub-menu is a list of metrics that hpcviewer can graph.

Each metric contains a sub-menu that lists the three different types of graphs hpcviewer can plot.

Plot graph. This standard graph plots metric values by ordered by their execution context.

Sorted plot graph. This graph plots metric values in ascending order.

Histogram graph. This graph is a histogram of metric values. It divides the range of metric values into a small number of sub-ranges. The graph plots the frequency that a metric value falls into a particular sub-range.

Note that the plot graph’s execution context have the following notation:

<process_id> . <thread_id>

Hence, if the ranks are 0.0, 0.1, … 31.0, 31.1 it means MPI process 0 has two threads: thread 0 and thread 1 (similarly with MPI process 31).

Currently, it is only possible to generate scatter plots for metrics directly collected by hpcrun, which excludes derived metrics created within hpcviewer.

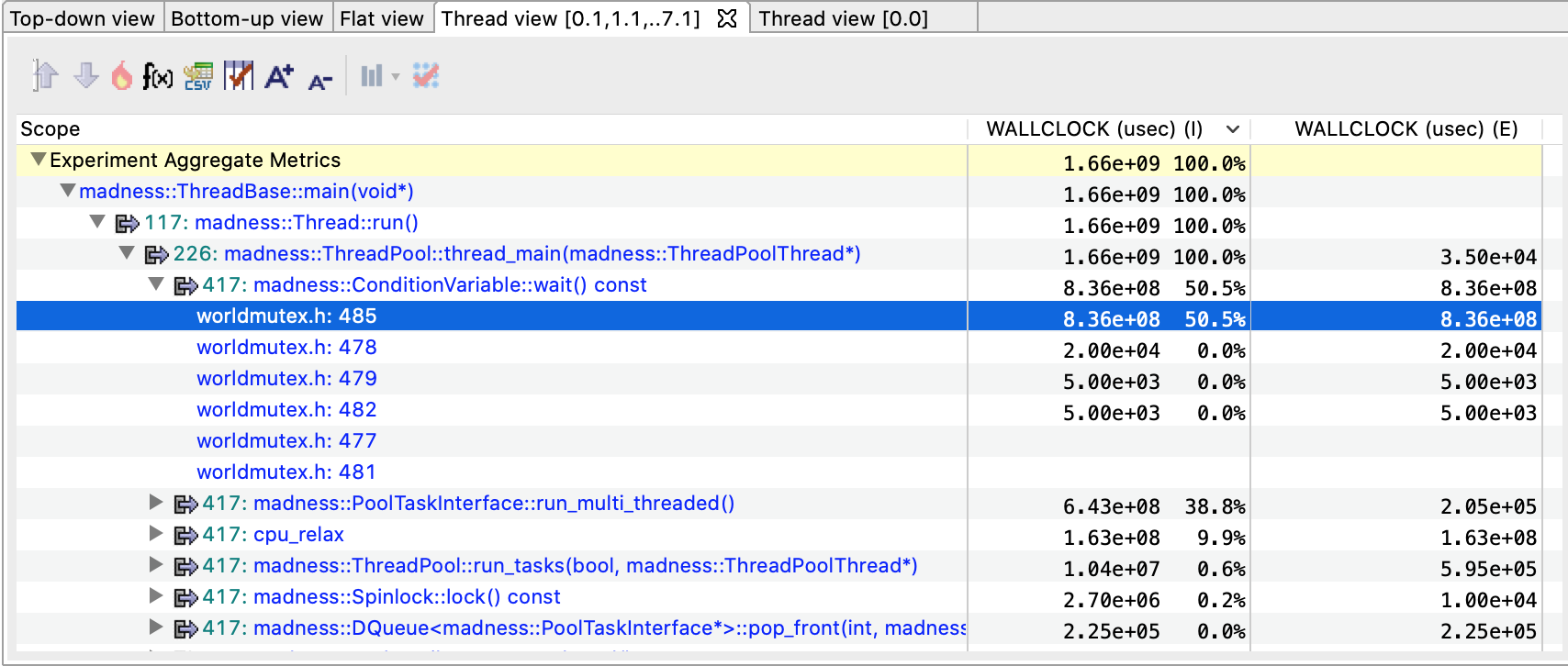

Thread View¶

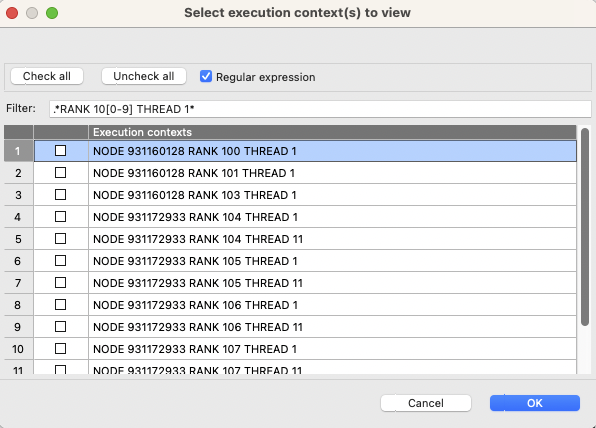

hpcviewer also provides a feature to view the metrics of a certain execution contexts (threads and/or processes) named Thread View.

A snapshot of a thread filter dialog. Users can refine the list of threads using regular expression by selecting the Regular expression checkbox.¶

Example of a Thread View which display thread-level metrics of a set of threads. The first column is a CCT equivalent to the CCT in the Top-down View, the second and third columns represent the metrics of the selected threads (in this case they are the sum of metrics from threads 0.1, to 7.1)¶

hpcviewer also provides a feature to view the metrics of a certain threads (or processes) named Thread View.

To select a thread or group of threads, you need to use the thread selection window by clicking  button from the calling-context view.

On the thread selection window (Figure 10.8), you need to select the checkbox of the threads of interest.

To narrow the list, one can specify the thread name on the filter part of the window.

Hence, to specify just a main thread (thread zero), one can type:

button from the calling-context view.

On the thread selection window (Figure 10.8), you need to select the checkbox of the threads of interest.

To narrow the list, one can specify the thread name on the filter part of the window.

Hence, to specify just a main thread (thread zero), one can type:

THREAD 0

on the filter, and the view only lists all threads 0 (such as RANK 1 THREAD 0, RANK 2 THREAD 0, RANK 3 THREAD 0 …).

Once threads have been selected, you can click OK, and the Thread view (Figure 10.9) will be activated. The tree of the view is the same as the tree from the top-down view, with the metrics only from the selected execution contexts. If there are more than one selected execution contexts, the metrics are the sum of the metric values.

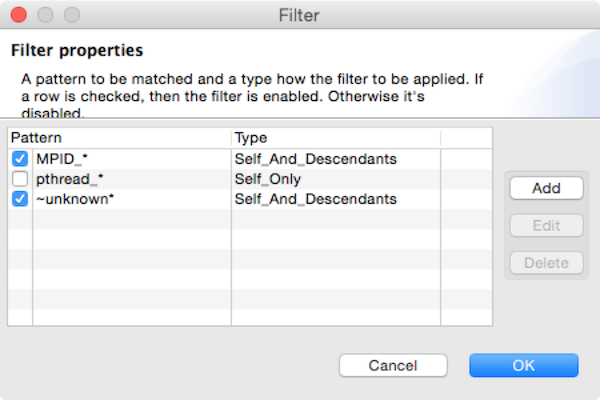

Filtering Tree Nodes¶

Occasionally, It is useful to omit uninterested nodes of the tree to enable to focus on important parts.

For instance, you may want to hide all nodes associated with OpenMP runtime and just show all nodes and metrics from the application.

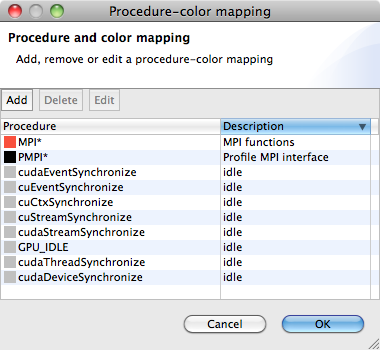

For this purpose, hpcviewer provides filtering to elide nodes that match a filter pattern.

hpcviewer allows users to define multiple filters, and each filter is associated with a glob pattern[16] and a type.

There are three types of filter: “self only” to omit matched nodes,

“descendants only” to exclude only the subtree of the matched nodes, and “self and descendants” to

remove matched nodes and its descendants.

Note

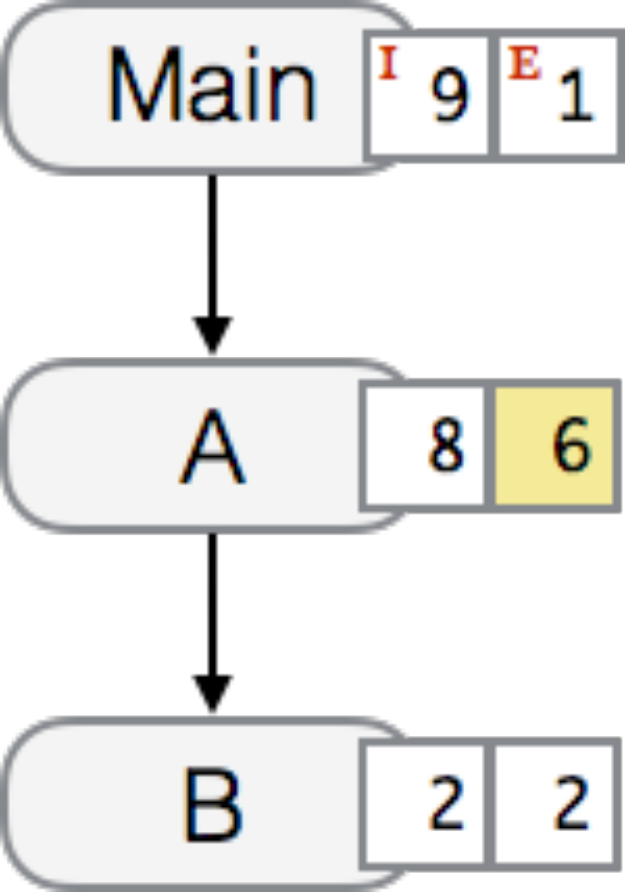

The original CCT tree.¶

The result of applying self only filter on node C.

Node C is elided and its children (nodes D and E) are augmented to the parent of node C.

The exclusive cost of node C is also augmented to node A…¶

The result of applying Descendants only filter on node C.

All the children of node C (nodes D and E) are elided, and the total of their exclusive cost is added to node C.¶

The result of applying self and descendants filter on node C.

Nodes C and its descendants are elided, and their exclusive cost is augmented to node A which is the parent of node C.¶

Different results of filtering on node C from Figure 10.10 (the original CCT). Figure 10.11 shows the result of self only filter,

Figure 10.12 shows the result of descendants only filter, and Figure 10.13 shows the result of self and descendants filter.

Each node is attributed with two boxes on its right. The left box represents the node’s inclusive cost, while the right box represents the exclusive cost.

The window of filter property.¶

- Self only

This filter is useful to hide intermediary runtime functions such as pthread or OpenMP runtime functions. All nodes that match filter patterns will be removed, and their children will be augmented to the parent of the elided nodes. The exclusive cost of the elided nodes will be also augmented into the exclusive cost of the parent of the elided nodes. Figure 10.11 shows the result of filtering node

Cof the CCT from Figure 10.10. After filtering, nodeCis elided and its exclusive cost is augmented into the exclusive cost of its parent (nodeA). The children of nodeC(nodesDandE) are now the children of nodeA.- Descendants only

This filter elides only the subtree of the matched node, while the matched node itself is not removed. A common usage of this filter is to exclude any call chains after MPI functions. As shown in Figure 10.12, filtering node

Cincurs nodesDandEto be elided and their exclusive cost is augmented to nodeC.- Self and descendants

This filter elides both the matched node and its subtree. This type is useful to exclude any unnecessary details such as glibc or malloc functions. Figure 10.13 shows that filtering node

Cwill elide the node and its children (nodesDandE). The total of the exclusive cost of the elided nodes is augmented to the exclusive cost of nodeA.

The filter feature can be accessed by clicking the menu “Filter” and then submenu “Show filter property”, which will then show a Filter property window (Figure 10.15). The window consists of a table of filters, and a group of action buttons: add to create a new filter; edit to modify a selected filter; and delete to remove a set of selected filters… The table comprises of two columns: the left column is to display a filter’s switch whether the filter is enabled or disabled, and a glob-like filter pattern; and the second column is to show the type of pattern (self only, children only or self and children). If a checkbox is checked, it signifies the filter is enabled; otherwise the filter is disabled.

Cautious is needed when using filter feature since it can change the shape of the tree, thus affects different interpretation of performance analysis.

Furthermore, if the filtered nodes are children of a “fake” procedures (such as <program root> and <thread root>), the exclusive metrics in Bottom-up view and flat view can be misleading.

This occurs since these views do not show “fake” procedures.

Note that the filter set is global that it affects all open databases in all windows, and it is persistent that it will also affect across hpcviewer sessions.

Convenience Features¶

In this section we describe some features of hpcviewer that help improve productivity.

Editor Pane¶

The editor pane is used to display a copy of your program’s source code or HPCToolkit’s performance data in XML format; for this reason, it does not support editing of the pane’s contents.

To edit your program, you should use your favorite editor to edit your original copy of the source, not the one stored in HPCToolkit’s performance database.

Thanks to built-in capabilities in Eclipse, hpcviewer supports some useful shortcuts and customization:

Find. To search for a string in the current source pane,

ctrl-f(Linux and Windows) orcommand-f(Mac) will bring up a find dialog that enables you to enter the target string.

Metric Pane¶

For the metric pane, hpcviewer has some convenient features:

Sorting the metric pane contents by a column’s values. First, select the column on which you wish to sort. If no triangle appears next to the metric, click again. A downward pointing triangle means that the rows in the metric pane are sorted in descending order according to the column’s value. Additional clicks on the header of the selected column will toggle back and forth between ascending and descending.

Changing column width. To increase or decrease the width of a column, first put the cursor over the right or left border of the column’s header field. The cursor will change into a vertical bar between a left and right arrow. Depress the mouse and drag the column border to the desired position.

Changing column order. If it would be more convenient to have columns displayed in a different order, they can be permuted as you wish. Depress and hold the mouse button over the header of column that you wish to move and drag the column right or left to its new position.

Copying selected metrics into clipboard. In order to copy selected lines of scopes/metrics, one can right click on the metric pane or navigation pane then select the menu Copy. The copied metrics can then be pasted into any text editor.

Hiding or showing metric columns. Sometimes, it may be more convenient to suppress the display of metrics that are not of current interest. When there are too many metrics to fit on the screen at once, it is often useful to suppress the display of some. The icon

above the metric pane will bring up the metric property pane on the source pane area.

above the metric pane will bring up the metric property pane on the source pane area.The pane contains a list of metrics sorted according to their order in HPCToolkit’s performance database for the application. Each metric column is prefixed by a check box to indicate if the metric should be displayed (if checked) or hidden (unchecked). To display all metric columns, one can click the Check all button. A click to Uncheck all will hide all the metric columns. The pane also allows to edit the name of the metric or change the formula of a derived metric. If the metric has no cost, it will be marked with grey color and it isn’t editable.

Finally, an option Apply to all views will set the configuration into all views (Top-down, Bottom-up and Flat views) when checked. Otherwise, the configuration will be applied only on the current view.

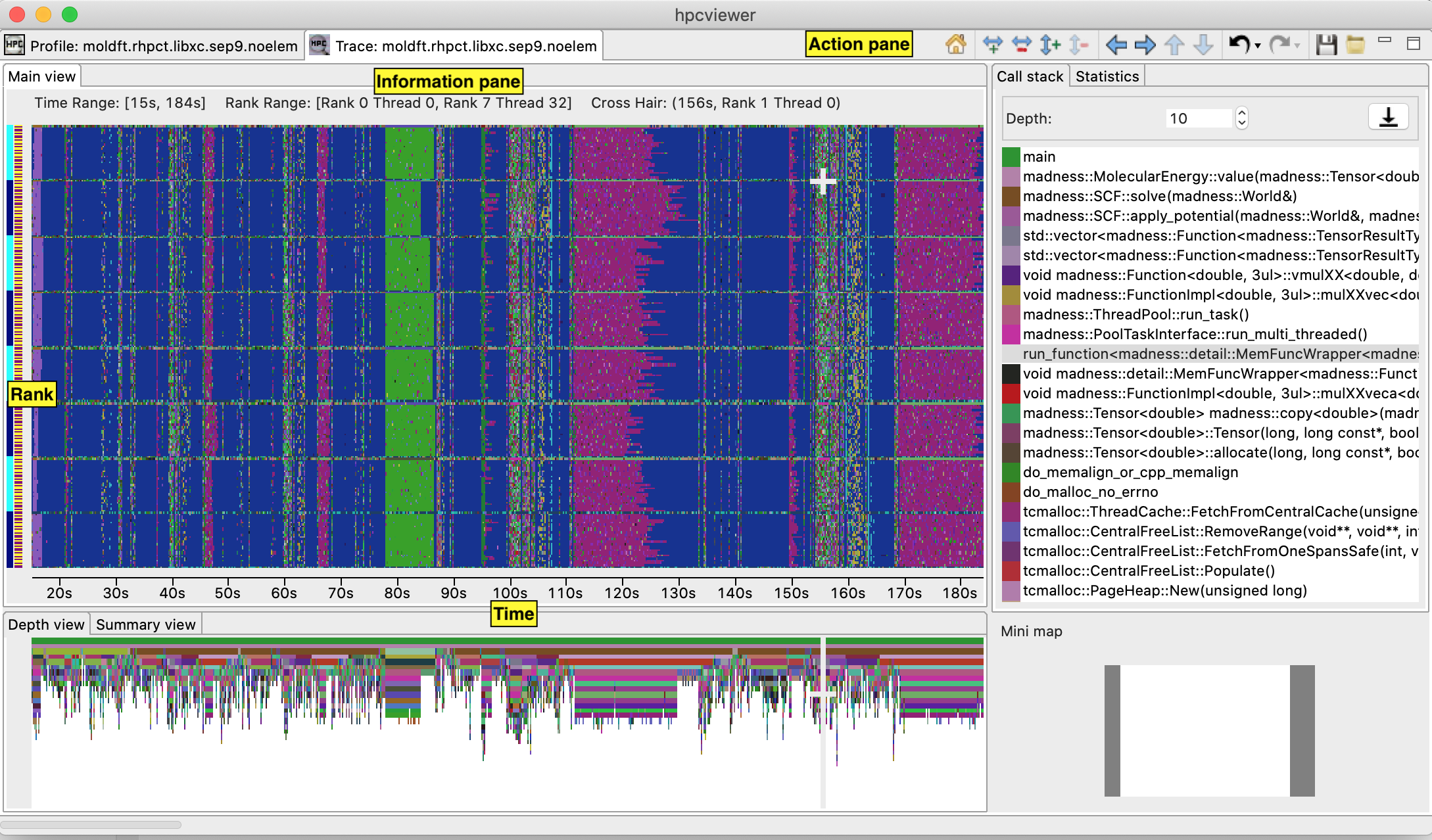

Trace view¶

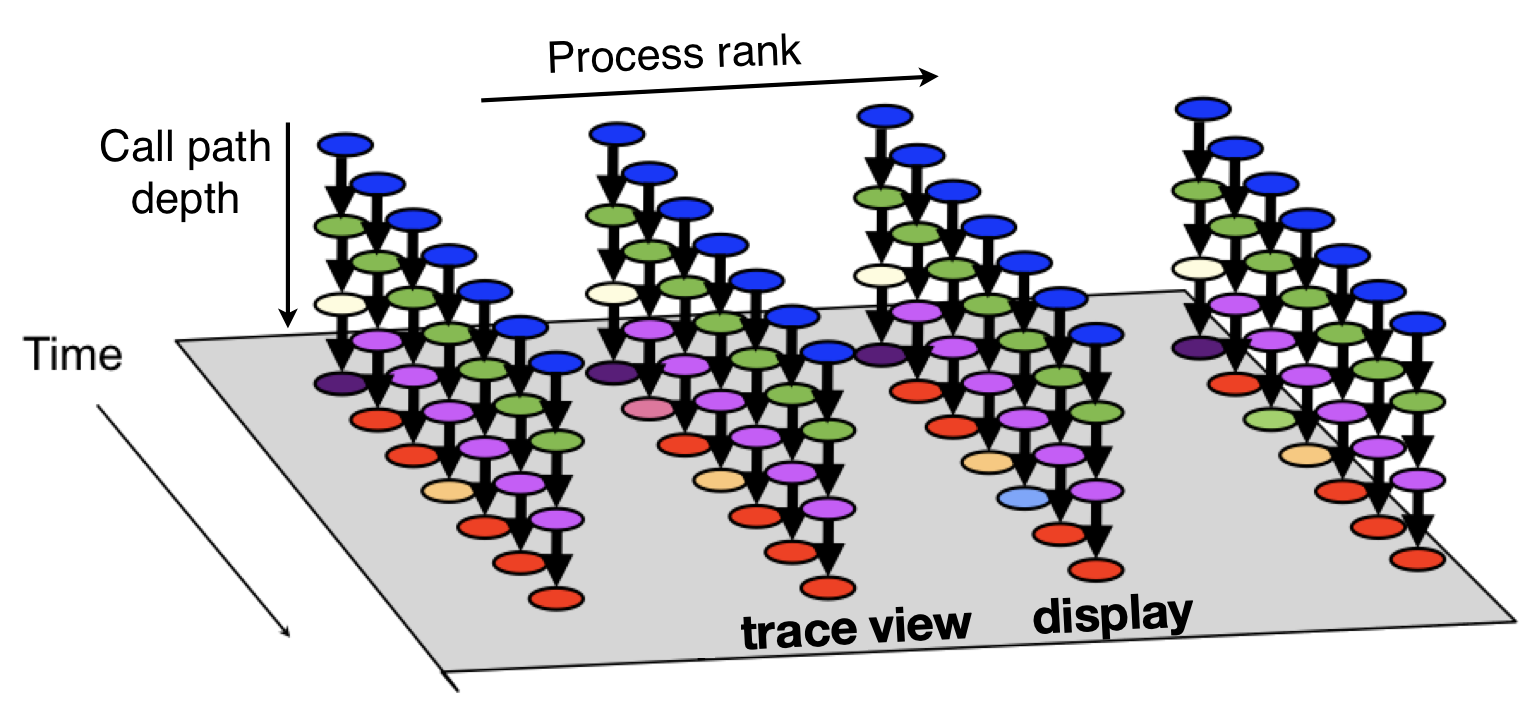

Logical view of trace call path samples on three dimensions: time, execution context (rank/thread/GPU) and call path depth.¶

Trace view (N. R. Tallent et al. 2011) is a time-centric user interface for interactive examination of a sample-based time series (hereafter referred to as a trace) view of a program execution. Trace view can interactively present a large-scale execution trace without concern for the scale of parallelism it represents.

To collect a trace for a program execution, one must instruct HPCToolkit’s measurement system to collect a trace.

When launching a dynamically-linked executable with hpcrun, add the -t flag to enable tracing.

When launching a statically-linked executable, set the environment variable HPCRUN_TRACE=1 to enable tracing.

When collecting a trace, one must also specify a metric to measure. The best way to collect a useful trace is to asynchronously sample the execution with a time-based metric such as REALTIME, CYCLES, or CPUTIME.

As shown in Figure 10.16, call path traces consist of data in three dimensions: profile (process/thread rank), time, and call path depth. A crosshair in Trace view is defined by a triplet (p,t,d) where p is the selected process/thread rank, t is the selected time, and d is the selected call path depth.

Trace view renders a view of processes and threads over time. The Depth View (Section 10.9.2) shows the call path depth over time for the thread selected by the cursor. Trace view’s Call Stack View (Section 10.9.4) shows the call path associated with the thread and time pair specified by the cursor. Each of these views plays a role for understanding an application’s performance.

In Trace view, each procedure is assigned specific color. Figure 10.16 shows that at depth 1 each call path has the same color: blue. This node represents the main program that serves as the root of the call chain in all process at all times. At depth 2, all processes have a green node, which indicates another procedure. At depth 3, in the first time step all processes have a yellow node; in subsequent time steps they have purple nodes. This might indicate that the processes first are observed in an initialization procedure (represented by yellow) and later observed in a solve procedure (represented by purple). The pattern of colors that appears in a particular depth slice of the Main View enables a user to visually identify inefficiencies such as load imbalance and serialization.

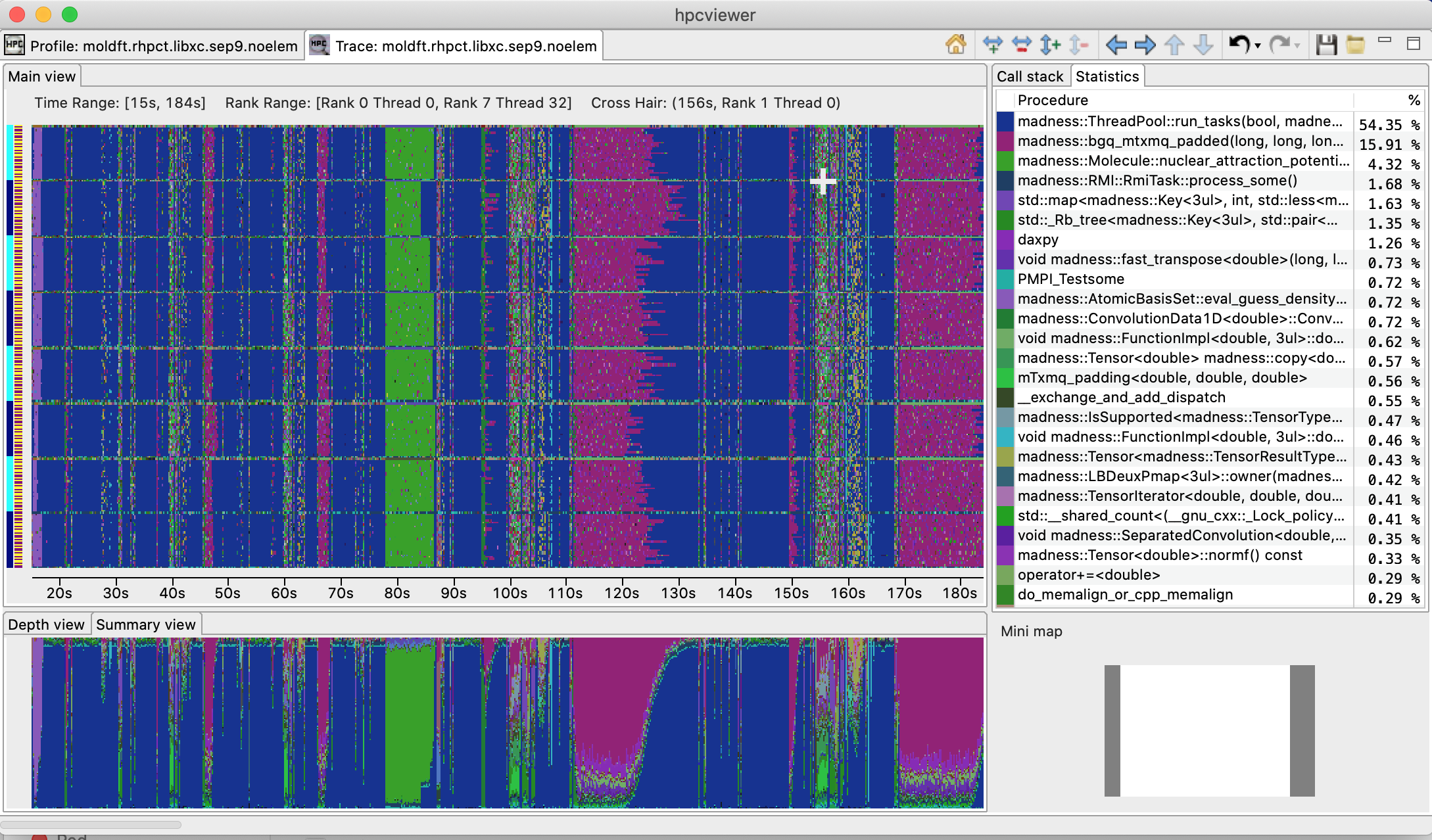

A screenshot of hpcviewer’s Trace view.¶

A screenshot of hpcviewer’s Trace view showing the Summary View and Statistics View.¶

Figures 10.17 and 10.18 show screenshots of Trace view’s capabilities in presenting call path traces. Figure 10.17 highlights Trace view’s four principal window panes: Main View(the main view), Depth View, Call Stack View and Mini Map View, while Figure10.18 shows additional two window panes: Summary View and Statistics View.

Main View (top, left pane): This is Trace view’s primary view. This view, which is similar to a conventional process/time (or space/time) view, shows time on the horizontal axis and process (or thread) rank on the vertical axis; time moves from left to right. Compared to typical process/time views, there is one key difference. To show call path hierarchy, the view is actually a user-controllable slice of the process/time/call-path space. Given a call path depth, the view shows the color of the currently active procedure at a given time and process rank. (If the requested depth is deeper than a particular call path, then Trace view simply displays the deepest procedure frame and, space permitting, overlays an annotation indicating the fact that this frame represents a shallower depth.)

Trace view assigns colors to procedures based on (static) source code procedures. Although the color assignment is currently random, it is consistent across the different views. Thus, the same color within the Trace and Depth Views refers to the same procedure.

The Trace View has a white crosshair that represents a selected point in time and process space. For this selected point, the Call Path View shows the corresponding call path. The Depth View shows the selected process.

Depth View (tab in bottom, left pane): This is a call-path/time view for the process rank selected by the Main View’s crosshair. Given a process rank, the view shows for each virtual time along the horizontal axis a stylized call path along the vertical axis, where ‘main’ is at the top and leaves (samples) are at the bottom. In other words, this view shows for the whole time range, in qualitative fashion, what the Call Path View shows for a selected point. The horizontal time axis is exactly aligned with the Trace View’s time axis; and the colors are consistent across both views. This view has its own crosshair that corresponds to the currently selected time and call path depth.

Summary View (tab in bottom, left pane): The view shows for the whole time range displayed, the proportion of each subroutine in a certain time. Similar to Depth view, the time range in Summary reflects to the time range in the Trace view.

Call Stack View (tab in top, right pane): This view shows two things: (1) the current call path depth that defines the hierarchical slice shown in the Trace View; and (2) the actual call path for the point selected by the Trace View’s crosshair. (To easily coordinate the call path depth value with the call path, the Call Path View currently suppresses details such as loop structure and call sites; we may use indentation or other techniques to display this in the future.)

Statistics View (tab in top, right pane): This view shows the list of procedures active in the space-time region shown in the Trace View at the current Call Path Depth. Each procedure’s percentage in the Statistics View indicates the percentage of pixels in the Trace View pane that are filled with this procedure’s color at the current Call Path Depth. When the Trace View is navigated to show a new time-space interval or the Call Path Depth is changed, the statistics view will update its list of procedures and the percentage of execution time to reflect the new space-time interval or depth selection.

GPU Idleness Blame View (tab in top, right pane): The view shows the list of procedures that cause GPU idleness displayed in the trace view. If the trace view displays one CPU thread and multiple GPU streams, then the CPU thread will be blamed for the idleness for those GPU streams. If the view contains more than one CPU threads and multiple GPU streams, then the cost of idleness is share among the CPU threads.

Mini Map View (right, bottom): The Mini Map shows, relative to the process/time dimensions, the portion of the execution shown by the Trace View. The Mini Map enables one to zoom and to move from one close-up to another quickly.

Main View¶

Main View is divided into two parts: the top part which contains action pane and the information pane, and the main canvas which displays the traces.

The buttons in the action pane are the following:

Home

: Resetting the view configuration into the original view, i.e., viewing traces for all times and processes.

: Resetting the view configuration into the original view, i.e., viewing traces for all times and processes.Horiontal zoom in

/ out

/ out  : Zooming in/out the time dimension of the traces.

: Zooming in/out the time dimension of the traces.Vertical zoom in

/ out

/ out  : Zooming in/out the process dimension of the traces.

: Zooming in/out the process dimension of the traces.Navigation buttons

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  : Navigating the trace view to the left, right, up and bottom, respectively. It is also possible to navigate with the arrow keys in the keyboard. Since Main View does not support scroll bars, the only way to navigate is through navigation buttons (or arrow keys).

: Navigating the trace view to the left, right, up and bottom, respectively. It is also possible to navigate with the arrow keys in the keyboard. Since Main View does not support scroll bars, the only way to navigate is through navigation buttons (or arrow keys).Undo

: Canceling the action of zoom or navigation and returning back to the previous view configuration.

: Canceling the action of zoom or navigation and returning back to the previous view configuration.Redo

: Redoing of previously undo change of view configuration.

: Redoing of previously undo change of view configuration.Save

/ Open

/ Open  a view configuration : Saving/loading a saved view configuration.

A view configuration file contains the information about the process/thread and time ranges shown, the selected depth, and the position of the crosshair.

It is recommended to store the view configuration file in the same directory as the database to ensure that the view configuration file matches the database since a configuration does not store its associated database.

Although it is possible to open a view configuration file associated with a different database, it is not recommended since each database has different time/process dimensions and depth.

a view configuration : Saving/loading a saved view configuration.

A view configuration file contains the information about the process/thread and time ranges shown, the selected depth, and the position of the crosshair.

It is recommended to store the view configuration file in the same directory as the database to ensure that the view configuration file matches the database since a configuration does not store its associated database.

Although it is possible to open a view configuration file associated with a different database, it is not recommended since each database has different time/process dimensions and depth.

At the top of an execution’s Main View pane is some information about the data shown in the pane.

Time Range. The time interval shown along the horizontal dimension.

Cross Hair. The crosshair indicates the current cursor position in the time and execution-context dimensions.

Depth View¶

Depth View shows all the call path for a certain time range [t_1,t_2] = {t | t_1 <= t <= t_2} in a specified process rank p. The content of Depth View is always consistent with the position of the crosshair in Main View.

For instance once the user clicks in process p and time t, while the current depth of call path is d, then the Depth View’s content is updated to display all the call path of process p and shows its crosshair on the time t and the call path depth d.

On the other hand, any user action such as crosshair and time range selection in Depth View will update the content within Main View. Similarly, the selection of new call path depth in Call Stack View invokes a new position in Depth View.

In Depth View a user can specify a new crosshair time and a new time range.

Specifying a new crosshair time.¶

Selecting a new crosshair time t can be performed by clicking a pixel within Depth View. This will update the crosshair in Main View and the call path in Call Stack View.

Selecting a new time range.¶

Selecting a new time range [t_m,t_n] = {t | t_m <= t <= t_n} is performed by first clicking the position of t_m and drag the cursor to the position of t_n. A new content in Depth View and Main View is then updated. Note that this action will not update the call path in Call Stack View since it does not change the position of the crosshair.

Summary View¶

Summary View presents the proportion of number of calls of time t across the current displayed rank of process p.

Similar to Depth View, the time range in Summary View is always consistent with the time range in Main View.

Call Stack View¶

This view lists the call path of process p and time t specified in Main View and Depth View. Figure 10.17 shows a call path of the current cross hair, and the current depth is 10 as shown in the depth editor (located on the top part of the view).

In this view, the user can select the depth dimension of Main View by either typing the depth in the depth editor or selecting a procedure in the table of call path.

Mini Map View¶

The Mini Map View shows, relative to the process/time dimensions, the portion of the execution shown by the Main View.

In Mini Map View, the user can select a new process/time (p_a,t_a),(p_b,t_b) dimensions by clicking the first process/time position (p_a,t_a) and then drag the cursor to the second position (p_b,t_b).

The user can also moving the current selected region to another region by clicking the white rectangle and drag it to the new place.

Trace view also provides a context menu to save the current image of the view. This context menu is available is three views: trace view, depth view and summary view.

Limitations¶

Some important hpcviewer limitations are listed below:

Limited number of metric columns. With a large number of metric columns,

hpcviewer’s response time may become sluggish as this requires a large amount of memory.Experimental Windows 11 platform. The Windows version of

hpcvieweris mainly tested on Windows 10. Support for Windows 11 is still experimental.Dark theme on Linux platforms. We received reports that

hpcvieweris not very visible on Linux with dark theme. Support for dark theme on Linux is still an ongoing work.Linux TWM window manager is not supported. Reason: this window manager is too ancient.

/

Unflatten

/

Unflatten  (only available for the Flat View):

(only available for the Flat View): /

Zoom-out

/

Zoom-out  :

: :

: :

: /

/

:

: :

: /

Decrease font size

/

Decrease font size  :

: